Writers, Robots, and Remote Work: Cheating in the Age of COVID-19

In no way do I advocate or encourage cheating in academic environments. References to businesses in this post are not endorsements, recommendations, or referrals; if anything, take them as warnings.

I was fortunate enough to attend a university where academic integrity relied heavily on the actions and the attitudes of students.

Collaboration on homework was encouraged, as long as the solutions you wrote were your own. Attendance was never mandatory, unless class discussions were involved. It was not only a norm but a requirement that exams be unproctored: instead of seating a class of students at the end of the term to watch them do their finals, instructors generally distributed the exams to be completed on the students’ own time, along with a self-imposed time limit and a due date. Often, an exam just felt like an extra-long homework assignment with no collaboration allowed.

It’s a very different model from the way most colleges conduct their courses. Caltech is not unique in this regard, but using an honor code to this degree, to entrust the integrity of each student’s grade almost completely to every other student’s honesty—classes were often curved—is not a common approach.

And we were grateful for it. Being able to take exams in our own preferred environments, whenever we felt most comfortable doing so, helped ease the stress of taking high-stakes exams, though it didn’t make the exams themselves any easier. We’d all left questions blank on many a final. Class-average exam scores were often abysmal. People still failed classes. But in a cruel way, it was a sign that the system worked, that despite the obvious difficulty of their assignments, students still held themselves accountable to be honest about their ability.

Coronavirus Curricula

There is some evidence to support the effectiveness of honor codes. As an alternative to more draconian measures like the threat of expulsion which increase the cost of cheating, it reduces the cost of not cheating and allows students’ own values—not to mention their need to collaborate with peers on other assignments—to take a larger role in their choices. In an environment where students trust that other students aren’t cheating, they no longer need to cheat just to play on a level field. In short, it’s to render irrelevant this question posed to the New York Times: “If My Classmates Are Going to Cheat on an Online Exam, Why Can’t I?”

It’s also made the transition to remote learning in the current global crisis just a little smoother. With a global pandemic pushing students and professors out of the classroom, many universities are facing a problem that Caltech has had ingrained in its policies for years: how do you conduct a test without proctors? Not all universities have given up on proctored exams, much to some students’ chagrin. But for many others, it’s an uncharted territory in which they’ve been thrust by a tiny global circumstance that’s already disrupted every other part of our lives.

The suddenness and pervasiveness of the situation has already inspired a flurry of articles and analyses on ways universities should adapt their courses. Some indicate that this is the time to establish honor codes. Others say that online exams shouldn’t have time limits. (At Caltech, we referred to them as “infinite-time exams,” and I think we all had a love–hate relationship with them.) Still others call for exams to be cancelled altogether.

Regardless of the approach, these changes mean that any exams that are held would now be subject to the same avenues for cheating that normally apply only to homework and take-home writing assignments. It also means that the pandemic environment didn’t really create a new market for companies catering to students looking to cheat. Instead, it made an existing business much more valuable: instead of only helping with homework assignments, the cheating economy can now take care of exams that could be worth 50% or more of a course grade.

Homework for Hire

The cheating economy is a 21st-century phenomenon of businesses that provide students with anything from answers to homework assignments to term papers and even a grade for the whole course. It’s as elaborate as any other industry whose potential customers number in the tens of millions and isn’t technically illegal. Companies offer freemium services on homework answers and experiment with different pricing models. There are blogs dedicated to ranking and reviewing essay-writing services. Startups rise and fall.

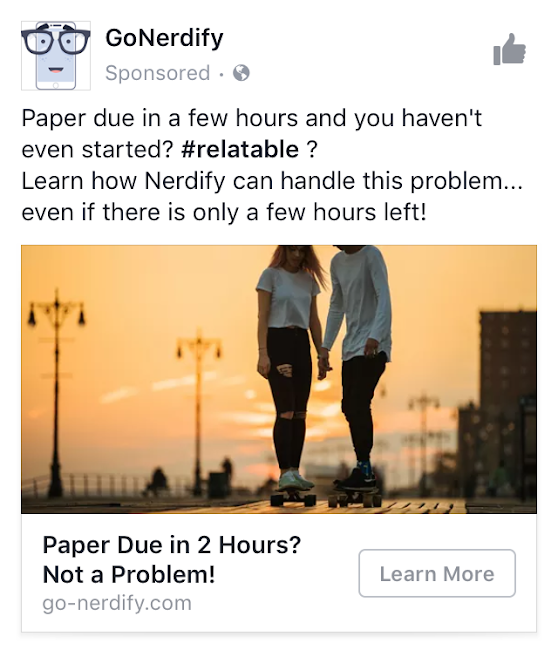

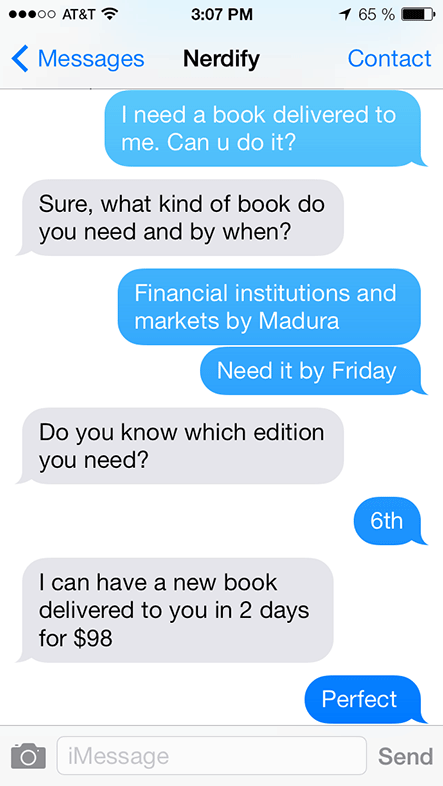

The companies that actually provide these services often cover themselves with a veneer of propriety, either by carefully avoiding any references to cheating or by explicitly stating that using their services for cheating is not condoned. Sometimes, they even show different content to students and teachers (more on this later). But everyone knows better. As this candid review of Nerdify points out, the existence of their “honor code”—a common feature among websites in the cheating economy—simply means that “they’re not responsible for the possible repercussions” of getting caught using their services.

And business is booming. With students now taking all their classes and exams online, there’s more of an opportunity to use online resources and more of a reason to pay for answers. Between mid-March and mid-May, the S&P 500 gained about 10% as it started recovering from the COVID-19 dip. Over the same period, the stock price of Chegg—perhaps the most prominent of the homework-help companies—more than doubled.

|  |

The Exposure Conundrum

An interesting feature of businesses engaged in activities that aren’t very palatable to the general public—such as essay-for-hire services—is that they face a particular challenge when it comes to growth: they need more people to know that they exist, but only the right people and nobody else. To most companies, advertising money spent on unlikely conversions is—at worst—money down the drain. To these businesses, it’s money spent actively undermining their own interests.

To put this into concrete terms, let’s consider Essays & Co., a small endeavor looking to provide completed term papers to overstressed students. They’ve found some localized success at a single school—perhaps a college their young founders are attending—but are looking to grow. As with any rowdy new upstart, Essays & Co. would like to get the word out and bring more students into its customer base. Normally, brand awareness would be their first success metric, with plenty of tried-and-true methods of achieving it at their disposal—product placement, billboards, TV spots, and so on. But unlike a normal business, Essays & Co. doesn’t want to tell everyone about their product. Doing so would invite regulatory scrutiny, parental rage, and countermeasures by suspicious teachers that negate the product’s own value.

It’s not hard to see the third issue in particular as an existential threat to Essays & Co. “Digital arms races,” in which two competing interests attempt to out-code, outmaneuver, and undermine each other, have become an established pattern in tech fields ranging from ad-blocking software to state-sponsored surveillance malware. In each case, two parties trade blows by updating their own software to be just a little cleverer each time, bypassing any new checks introduced by the other side’s iteration—a vortex of slightly more benign-looking ads, slightly more diligent ad blockers, slightly better obscured trackers, slightly more aggressive security teams.

It’s a costly process, one that can quickly drain away engineering hours—so costly, in fact, that it was cheaper for Google (in the ad-blocking case) to just pay the ransom. Getting into a mess like this could spell the end for our little essay-writing company.

This is where targeted digital advertising comes into the picture.

Sniper Marketing

In general, the strategy of advertising narrowly to customers for whom it would make a difference—such as in targeted sidebar ads—is known as pull marketing. This is in contrast to push marketing, in which the goal is to carry a message to as broad a swath of the population as possible—such as on a billboard or TV spot. This is not a novel concept, nor is pull marketing uniquely a digital phenomenon: for example, posting a flyer about an oil-change business on the window of an auto-parts store would be cross-promotion, a form of traditional pull marketing.

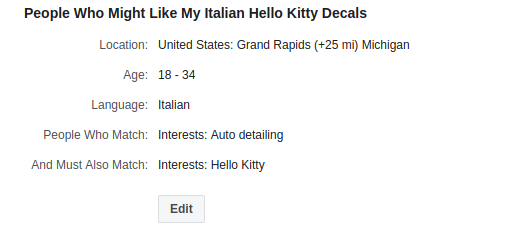

What companies like Google and Facebook have provided to their business customers, then, is not so much a new way of thinking about advertising as a radically efficient means of applying that thinking. Thanks to the incredible amount of data that these companies collect about their users, a customer can target not just people who are interested in maintaining their car—as in the flyer example above—but young people who are interested in maintaining their car, like Hello Kitty, and speak Italian.

(An aside: I don’t really buy the characterization of Google and Facebook as companies that “sell your data” because it implies a more nefarious business than the one they actually conduct. They hold plenty of information about us, but it’s used to carry advertisers’ messages to us, not to provide it to the advertisers. Nobody’s paying Facebook money to learn what hobbies we have; we don’t accuse the USPS of “selling our locations” when they deliver parcels. How much did working at Facebook shape my opinion on this matter? Who knows.)

The pinpoint precision of the Internet giants’ advertising engines has led to controversy in the past. In 2019, Facebook was slapped with a discrimination lawsuit after the Department of Housing and Urban Development found that a combination of the ability to buy certain types of ads on the platform (for housing) and the ability to target those ads to exclude certain groups of people (by affinity to an ethnicity or national origin) led to ads served in violation of the 1968 Fair Housing Act. A few years prior, a study found that identifying a Google user with one gender or another results in different offerings of employment ads—a recipe for equal-opportunity violations.

Nonetheless, numerous businesses—cheating-economy or otherwise—benefit from targeted digital advertising. The colossal success of Google and Facebook is a testament to the value of identifying customers who might be swayed by advertisements, precisely separating them from the rest, and then putting all the eggs (in this case, advertising dollars) into their basket. For Essays & Co., the need is even stronger.

We Know Who You Are and Where You’ve Been

But even the precise targeting offered by the massive online advertising platforms can’t prevent the word from reaching people the company doesn’t want to reach. Students might let slip or report on these services to their teachers. Diligent educators might look up these services for themselves, to keep themselves informed and ahead of dishonest students.

Fortunately for Essays & Co., there are ways to control even information spreading by word of mouth.

There are two pieces of web technology that are particularly relevant here: fingerprinting and indexing. Fingerprinting is a set of techniques that allow websites (and, by extension, the companies that run them) to uniquely identify their visitors. By combining signals such as your browser version, screen size, time zone, and even which fonts and browser extensions you have installed, companies can track which pages get accessed by someone with that unique combination—you—on their site and even across other sites. Indexing describes a process in which a program (known as a crawler or robot) builds an index of known sites by loading pages, scanning for links, loading those pages, and so on. It’s how services like Google build their massive records of keywords and webpages, reconstructing the landscape of the Internet in a way that makes searching possible.

In tandem, these two concepts allow us to ensure that one set of users—say, students—see one set of pages, while another set—teachers—see a completely different set.

This isn’t just a hypothetical scenario. Nerdify is a real-life Essays & Co. founded in 2015 (though it would claim otherwise for plausible deniability). This appears to be exactly how it approached marketing in its early years, and their model offers an excellent glimpse into how such a configuration works.

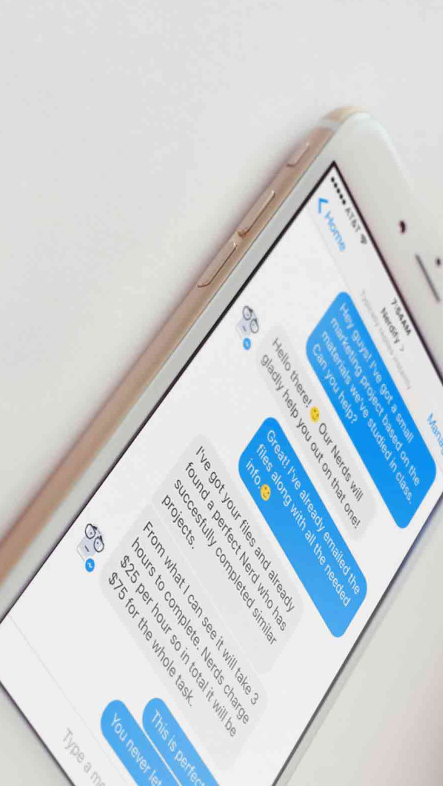

- First, we create two sets of pages. One set is for the students and can describe in moderate detail how one would use the service to cheat. The other is for the teachers, and should appear more benign. (In Nerdify’s case, the first site was located at go-nerdify.com and the second at gonerdify.com, without the hyphen.)

- Second, we advertise heavily and specifically to college students through Facebook. Our ads take them to the students’ site, and when they get there, the site uses their browser fingerprint to verify that they’re in the right demographic before showing the more explicit references to cheating.

- Third, we use crawler instructions to prevent Google and other search engines from indexing the students’ site while actively promoting the teachers’ site to the same search engines. This way, people who find our service on their own, by search, only ever come across the teachers’ site.

Abusing robots.txt for Fun and Profit

Crucially, the third step—strategic indexing—relies on a little file called robots.txt. This is a standardized file that allows a website to tell crawlers what they are and aren’t allowed to index. Take a look at the robots.txt files that Nerdify used for its student-friendly and teacher-friendly sites:

User-agent: *Disallow: /User-agent: YandexDisallow: /User-agent: GooglebotDisallow: /User-agent: googlebot-imageDisallow: /User-agent: googlebot-mobileDisallow: / | User-agent: *Allow: /Disallow: /p/Disallow: /r/Sitemap: http://gonerdify.com/sitemap.xml |

In the first, Nerdify is instructing all crawlers to avoid the entire site (signified by /). In the second, Nerdify explicitly allows the entire site to be crawled (with the exception of two utility folders), and even offers a helpful sitemap for the crawlers to get their bearings.

The result—at least in theory—is a clean segregation of visitors into two camps. A large number of students discover Nerdify through Facebook ads and read about how they can pay for their homework to go away. Some of them sign up. Others move on. A few zealous ones report the service to their teachers, who investigate the situation with concern. The teachers search for “Nerdify” on Google, only to find a service that offers “book delivery.” Suspicion evaporates and money is made.

|   |

So, What Now?

Arguably, web technology and the remote learning opportunities it provides saved higher education programs while COVID-19 ravaged the world. We’ve been forced to seriously consider a mode of learning that had been adopted mostly by university extension programs and struggling, oft-criticized for-profit schools. But if this has been a trial by fire of massive-scale distance learning, the ruling seems to hold that some incarnation of online learning, likely integrated with traditional classrooms, is here to stay.

And with the “new normal,” as people seem to be calling it, the role of the cheating economy continues to grow. The landscape of web technology evolves rapidly, and so do the companies that were born to exploit it.

So what can we do? We’ve seen that purely technical solutions are fragile and can be quickly defeated—plagiarism-checking software by essays on demand, digital proctoring software by a whole host of different methods—and that the big names in the industry are plenty savvy when it comes to legal pretext and tech tricks.

In the end, I don’t think the approach should be any different from what it’s always been: by structuring courses and student relationships to reduce the pressure to cheat, rather than by trying to appeal to morality or to catch the cheating after the fact. There probably isn’t a single right answer, but we do have plenty of promising pathways and now a wealth of time with an unwitting natural experiment by which to try them out. After all, we’re all here to learn, aren’t we?

Nice webpage and interesting reading